It’s been 200 years since Jane Austen’s novels were published and yet, Jane mania is still in the air. If you don’t believe me, just look to the 12ft inflatable Mr. Darcy (eerily favoring Colin Firth) floating in London’s Hyde Park last summer. (Clearly, I’m not the only one who loves the 1995 Pride and Prejudice miniseries.)

Modern Janeites remain captivated, but do we know why Austen’s so irresistible? Do we long for a more romantic time? Do we still have a sense of the meaning behind her novels? We tend to only emphasize the romantic plots and ignore what makes her truly remarkable–her insightful examination of human virtue.

Make no mistake, Austen exquisitely fashions a good love story and readers have been delighted for centuries with her characters who are, in the words of Mr. Bennet, “crossed in love,” as they travel a winding road to their matrimonial fate. But it’s not merely the classic romance that entices Janeites, it’s her meticulous and brilliant illumination of virtue that gives depth to her stories and characters.

Am I reading too much into these delightful works of fiction? Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre doesn’t think so. In his masterful work After Virtue, he claims, “Jane Austen is in a crucial way…the last great representative of the classical tradition of the virtues.” It might sound dry to consider Austen’s novels in this way, but Austen’s philosophy of virtue is what makes her so exciting and alluring to us in the 21st century.

In an era that finds a discussion of virtue laughable, Austen hearkens back to a world in which character is prized above charm, and constancy trumps a magnetic personality. Heroines like Elizabeth Bennet demonstrate that virtue and attractive spunk aren’t mutually exclusive. And as we can see by her portrayal of characters like Fanny Price, heroine of Mansfield Park, Austen is more impressed by strength of character than the most alluring and sparkling charm (ahem, Mary Crawford.)

These days, the best modern romcoms share some basic plot points with Miss Austen. Think Pride and Prejudice and You’ve Got Mail, complete with a few Elizabeth Bennet/Mr. Darcy references in Meg Ryan and Tom Hanks’s banter. The two romantic leads dislike each other at the beginning of the movie and then fall in love by the time the credits roll. And then we have modern revamps of Austen plots such as Clueless (loosely) based on Austen’s Emma. But typically the plot lines and the characters of romcoms don’t overlap. And I don’t think I’m the only one who finds most of them forgettable. What is it about Miss Austen’s works that keep us coming back for more while most modern romantic comedies end up unsatisfying?

For the most part, the leading ladies can’t hold a candle to Austen’s heroines, but it’s the male leads in modern romantic comedies who really flop. Austen’s noble heroes have little in common with these heartthrob charmers (at least I think we’re supposed to find them charming?). Most romcoms seem to have one of two “types” as the male lead. You have the Irresponsible Loser who becomes somewhat reformed in order to win the girl (think Fool’s Gold with Matthew Mcconaughey and Kate Hudson, on second thought don’t think Fool’s Gold because it was dreadful). Or you have the Egotistical Womanizing Jerk the leading lady despises but can’t deny her inexplicable attraction to. (Think The Ugly Truth with Katherine Heigl and Gerard Butler. Dreadful is probably too generous a descriptor.)

It’s almost comical to compare Mr. Knightly or Fitzwilliam Darcy to the cads being paraded as heroes in modern romcoms. But what makes them different? Austen’s main men possess virtue that only fully revealed over time and in context of their community, something difficult to grasp in our quick-paced, isolated culture.

Only after visiting his estate of Pemberley does Elizabeth get a better picture of Darcy’s true character. Sure, touring the beautiful mansion and extensive grounds didn’t hurt her impression. But the description from his housekeeper of Darcy’s kindness and goodness also began to open her eyes. I’ve always heard that you can tell a lot about a man from how he treats the server at a restaurant. Perhaps the same is true about wealthy Regency era British guys and how they treat their housekeepers. Treating someone with respect and kindness when there’s nothing in it for you reveals good character.

Darcy’s selflessness and devotion come to the surface near the end of the novel when he saves the Bennet family from scandal and ruin at great personal cost to himself. Time, community, and action are what reveal the soul of Austen’s heroes.

In the fullness of time the villain, however, reveals himself to be exactly the opposite of the hero. Although often charming and attractive upon first impression (unlike the aloof and at first disagreeable Darcy), the rake is slowly unmasked by how his selfish decisions impact his relationship to his community.

Take Sense and Sensibility, a novel with two leading ladies, the prudent Elinor Dashwood and her passionate younger sister, Marianne. The rake of the novel is Willoughby, a handsome and charming young man with a love for poetry who wins the heart of the impetuous Marianne on their first meeting. Everyone finds him pleasant and delightful. But when his family cuts him off after it comes to light that he fathered a child out of wedlock and abandoned the mother, he breaks Marianne’s heart and marries a far wealthier young lady for financial gain. His charm concealed his true character of extreme selfishness and weakness.

The star of the modern romcom is quite similar to “the cad” type found in Austen’s tales, like Wickam of Pride and Prejudice, Willoughby of Sense and Sensibility, or Henry Crawford of Mansfield Park—handsome, charming, and selfish. Willoughby literally sweeps Marianne off her feet the day they meet because she’s sprained her ankle. A perfect meet-cute for the modern romcom, but the superficial romance doesn’t merit true love.

By the end of an Austen novel we despise the selfish rake character, but the modern romcom makes The Irresponsible Loser or the Selfish Womanizing Jerk the hero, and attempts to convince us that the successful, clever, and responsible heroine will be happy sharing a life with the (hopefully) reformed male lead. If this is the fare offered to us, no wonder we re-read Austen year after year and wait eagerly for each new film adaption!

We’re so entrenched in the modern narrative of infatuation parading as love that it’s hard to spot a story of true love when we see it. Colonel Brandon, the real hero in Sense and Sensibility seems old and boring to us in comparison to the dashing, poetic young Willoughby. Like Marianne, it takes us until the end of the novel to see Brandon for what he is: a man worth spending your life with. How can we be bored? Is a patient, selfless love that puts the beloved’s happiness above his own desires not romantic enough for us? I think it’s hard for a modern reader not to think, “But if only Willoughby had REALLY reformed.” (Or in Mansfield Park, if only Henry Crawford had really reformed.) But unlike the modern reader, at least Marianne is clear-headed enough to see that after Willoughby’s true colors emerged, the only thing more painful than being abandoned by him would have been to be married to someone so selfish.

In the excellent and beautiful film The Painted Veil, based on the novel by M. Somerset Maugham (which I haven’t read and differs from the film on some major plot points), a young doctor and his unfaithful wife move to rural China amidst seemingly insurmountable marital strife. She finds him dull and lifeless, he finds her silly and selfish. Yet, as she sees him through the eyes of his patients and the community at large, she begins to respect his skill, wisdom, and compassion.

Their relationship begins to change from spite to warm friendship. She has an epiphany when a male friend explains to her that his lover is attached to him because he is “a good man.” She scoffs, “No woman ever fell in love with a man for his virtue!” And suddenly she realizes that she has done just that and it is her husband’s character that has garnered her respect slowly and deeply won her love.

We may claim that virtue won’t win us over. But our love for Austen belies us.

We’ve been shown cardboard cut outs of love, when we want the real thing. We’ve been fed a fast-food version of romance and we want a fine meal with a glass of red wine. Jane Austen does not remain popular because she wrote the type for the modern romance but because she writes the antithesis of it: a love based on virtue instead of infatuation. That’s where Austen delivers and why she’ll remain a guide to the human heart and soul for another 200 years.

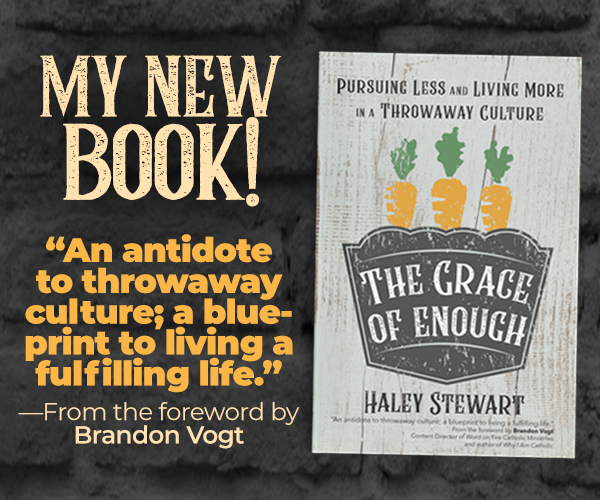

I think you would LOVE this book, if you haven’t already read it. I highly recommend it. I was nodding all the way through…

http://www.amazon.com/Jane-Austen-Guide-Happily-After/dp/1596987847

I haven’t even heard of that! Thanks, Kate, I will check it out!

Yes, yes, yes! Wonderfully articulated and true! I was thinking of this recently when re-reading Emma – Austen’s protagonists often praise ‘open’ characters who are immediately likeable and confiding . . . but appreciation for discretion comes with time.

That’s so right, Arenda! I just re-read Emma, too, and that is a perfect explanation of that theme of “discretion.” Emma learns that maybe Jane Fairfax had the right idea after all 😉

YES! You’ve made me want to start a Jane Austen (and the like) book club! 🙂 I’m always impressed with the way you–and your dear husband–express yourselves on love and marriage. And so pleased to encounter other women who understand that virtue and feminism go hand-in-hand! You share quite a lot of wisdom for someone so young. Keep up the good work! <3

That is so kind, Pat! Thank you. <3

I love the captioned pictures! Most people would have automatically used shots from the movies. Props for going out of your way to do something clever! 🙂

Haha! Thanks! I got a kick out of making those. Also, I’m super scared of using copyrighted photos. You can get in big trouble. And these are so old that they were in the public domain (yay!).

I love everything in this article! Jane Austen, romance, philosophical discussion of virtues, modern social application… ahhhh. It’s my blog-post sweet spot. (Which is extra nice since I’m missing out on actual sweets thanks to this Whole30 thing!)

Haha! Thanks, Jessica! This is my favorite kind of post to write 😉 And holy cow, I’m ready for cheesecake. At least we’re halfway done!

I totally agree! Though I think someone should write a follow up post: Modern Romantic Comedies with Male Leads Who Aren’t Dreadful. (Also, modern novels.)

I love that and it’s a brilliant idea 😉

Oh, please do read The Painted Veil! It was such a good book!!

So, here’s the most intelligent comment you’re ever going to read on this subject–That’s why I like Frozen for my kiddos. I feel like it’s a Disney version of a classic Jane Austen story. Hans seems like such a gentleman and sweeps poor Anna off her feet, but he’s really just a cad. It’s loyal, though rough around the social edges, Kristof who ends up being the true gentleman.

See? Mind blowing. 😉

I like that, Virginia! I’m a big fan of Frozen. The other day Lucy was telling me, “You can’t marry someone unless you just met him. Unless it’s twue wove.” So we might need to have a little chat about Frozen, haha.

LOL yes – “Wove, twue wove” needs a bit of time to differentiate itself from infatuation. Speaking of twue wove, your thoughts really illustrate how the Princess Bride is a fairy tale/allegory, and *not* a romance. The romantic leads have none of the revealed virtue of Austen’s characters or even the personality of modern fall-down knock-offs. I never thought of it that way!

Loved this article. I can say the same thing about Wives and Daughters and North and South, though they are not NEARLY as widely circulated as Austen. (A damn shame.) I’m currently watching the miniseries of Middlemarch… I have yet to see if the men in that story are so masterfully portrayed. I do, however, have high hopes of George Eliot.

I agree that, in modern romantic novels (I’m thinking of fan favorites such as Twilight and Frozen), we as a culture have lost sight of the core of men’s character and virtue. The men of these stories have no substance, no soul. I’m appalled by the (often, though, not in the case of Twilight) fleshed out, strong female lead who is supposed to fall in love with this two-dimensional loser. Love is all glam. Like macaroons: beautiful, but as light as air and overly sweet.

Even in Becoming Jane, James McAvoy’s character is really quite the loser. Attractive, exciting, but lazy! Looking back at it, I can’t really recall any virtues that he might have possessed. I have a hard time believing Jane could have loved someone like him, but I suppose we were all fools in love once. 🙂

Sorry, I know Frozen is a favorite, but I think Kristoph is a total loner/loser. Good thing Hans turned out evil so Ana didn’t have to make a CHOICE *gasp* like Marianne.

I feel the same way about Becoming Jane! I mean, don’t get me wrong, I’ve seen it like 5 times. But I agree that I’m confused what Jane would have seen in him…apart from his super handsomeness.

I never saw Becoming Jane, because the trailers suggested McAvoy’s spark is what gave fire to Austen’s too-tame writing, and I was so offended I called a one-lady silent boycott. 😉 Too-tame? After reading her short-stories from her teen years, you rather get the impression she broke her wrist reining in her spirits to the courtship novel!

I love this article, Haley! Thanks so much for writing it!

Thanks, Heather!

Haley, this is perfect! These are exactly the words I’ve been trying to say to my youngest sister who, at 16, is almost exclusively attracted to Wickams (and has NO appreciation for Jane Austen). Thank you for articulating this so clearly – well said!

Thanks, Willow 😉

Yes, Haley read Wives and Daughters and North and South if you haven’t! So great!

Both are so good! Read them last year 🙂

I love everything about this!! (I am new to your blog and Twitter feed, and I have to say I’m a huge fan. You are a kindred spirit, which is rare for me to find on the interwebs!) Growing up, I used to write in my journal how I wanted my own Mr. Knightley; I loved his serious huffiness, trying to keep her on track but having such a weakness and adoration for her at the same time. I find so many uplifting, gentle themes in Jane’s work: forgiveness of faults, softening of edges, and a desire to help one’s partner grow. Much can be learned from her! …And I will also forever be in her debt for the work that led Colin Firth to become a household name, at least in my house. 😉

Mr. Knightley is my FAVE. Thanks for stopping by and introducing yourself, Annie!

I love this post! I also am constantly re-reading Jane Austen’s novels and watching the 1995 P&P a billion times (I’m on my third copy of it because I’ve watched it so much). Mansfield Park is my favorite book, but I love all of them. Thank you for articulating what I’ve always had a hard time explaining to people. =)

I love it when there’s others Mansfield Park lovers out there! <3

I agree! And now I really want to go watch Pride and Prejudice (but which version?). And it reminds me why I love my husband. I mean yes, he’s super cute and very sweet. But some of my favorite qualities are that he’s extremely ethical, industrious, and respectful. Those last three qualities are ones that outweigh every other thing, and make me feel like I’m the luckiest of ducks.

Love that, Lauren! Sounds like a keeper 😉

Haley, you write SO well! This captured something for me that I hadn’t put into words about my husband — not your modern day romantic hero, but a man of true virtue. I’m so lucky! And now I’m dying to go pick up Mansfield Park again too.

I just re-read it this year and it was so good! Daniel’s listening to the audiobook, haha.

Yes! Another aspect I love about Austen is her ability to poke fun at silly and often selfish behavior (Mrs.Bennet, Anne’s sister Mary, Marianne and her mother’s sensibilities).

When people don’t like Austen, I wonder if they are just missing her humor. She is SO FUNNY.

Yes! Yes! Yes! Great post! I’ll have to check out that book by MacIntyre. The things you said about it remind me so much of my favorite book on JA: Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues by Sarah Emsley. Truly the best book on Austen’s novels I’ve read. I did some posts on her book here: http://thebowerofbelle.blogspot.com/p/jane-austen.html I love it when you talk books on your blog, especially Austen’s. 🙂

I’m joining this party a bit late, but Haley, do you read the blog darwincatholic? The wife of the duo, Mrs. Darwin, just finished her modern take on Mansfield Park that really emphasizes the virtuous aspect of Austen’s work. It’s really well done, and she’s looking to publish it. Read it when you have some free time!

A link to the book postings:

http://darwincatholic.blogspot.com/2014/08/stillwater-index.html

A discussion of how and why she wrote as she did:

http://darwincatholic.blogspot.com/2014/09/stillwater-55-afterword.html

This post reminds me of a section from Persuasion when Anne is considering her friend’s assertion that Mr. Elliot plans to ask her to marry him. Here are her thoughts:

“She distrusted the past, if not the present. The names which occasionally dropt of former associates, the allusions to former practices and pursuits, suggested suspicions not favourable of what he had been. She saw that there had been bad habits: that Sunday travelling had been a common thing; that there had been a period of his life (and probably not a short one) when he had been, at least, careless on all serious matters; and though he might now think very differently, who could answer for the true sentiments of a clever, cautious man, grown old enough to appreciate a fair character? How could it ever be ascertained that his mind was truly cleansed?”

How often do we, in modern times and in modern entertainment, wonder about the actual mental cleanliness of the ‘reformed bad boy’? The idea of valuing virtue versus valuing the edgy, potentially dangerous romantic lead is the big difference!

My central problem with Jane Austen’s novels is not with her characters (which are well-made), or with her story lines (which have quality, and are well-conceived), or even with her subject-matter. My real problem with Jane Austen is her abominable writing style, which – to me at least – is by far the most stifling, stultifying, impenetrable prose I have ever seen. It is fantastically dull and difficult to read. The only writing I know of which is more difficult is that found in Philosophy – for example, in Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, in which the writing is far, far more difficult to read than in Jane Austen’s work. But as far as pure literature goes, Austen’s writing is the worst. I have literally never seen anything else like it.

Writing about the Landed Gentry (aristocracy) of Regency England as Austen does is not a bad thing, and can be quite interesting. It’s how Austen has chosen to go about doing so that drives me absolutely up the wall. There seem to be two main problems here: Austen’s horrendously difficult, technically-demanding sentences, and what she chooses to describe with her horrendously difficult, technically-demanding sentences. Her characters (frequently females, but quite often the males too) seem absolutely obsessed with the apparent “doilies and Dalmatians” minutae of aristocratic life in general – with literally hundreds and hundreds of pages devoted to this. Never before have I seen such an attitude carried to the extremes it is here.

Basically, by the end of every Jane Austen novel, the reader is left staring at one big doily. That’s really all her prose style amounts up to, in the end. Characters frequently worry about just where the napkins are placed next to the forks, or just how perfectly the doilies are adjusted on the tea tables; did the neighbours see the doilies? Just what did they think about the doilies? How did the doilies affect the social advance of the family in general? Could Mrs. Such-And-Such have been impressed by the doilies to such a degree as is thought suitable by everyone else to the exact correct extent (but not quite TOO much, as is proper)? Could the doilies have been adjusted just a little more to one side, and if so, what shockwaves would this have sent throughout polite society? What must be felt about the doilies? What MIGHT POSSIBLY have been felt about the doilies? What COULD NOT POSSIBLY have been felt about the doilies, and in what capacity, and to what degree, and in what conditions, by absolutely everyone? Could the fate of the world (not to mention society itself) really rise and fall on the state of a doily?

Never before have I seen such massive intellectual power pumped into obsessions with wishy-washy aristocratic minutae. It is literally mind-blowing to see this kind of small-mindedness expanded out into a full novel, and then to be dignified by that term. Do we really have to know just where all the forks and spoons are, and everyone’s reaction to them, in the correct sequence and societal order? Must we read fifty pages on each and every stitch of knitting that the women do, and exactly what ramifications each knitted garment has for society as a whole? Is it REALLY that essential that the characters discuss (in obsessive-compulsive detail) every single other character’s reaction to the latest tea-party, or to every last tiny inconsequential comment of even the smallest note whatsoever, over hundreds and hundreds of pages? Because that, unfortunately, is what the majority of Jane Austen’s writing consists of (or at least, of things of a similar nature) – on and on and on and on and on, with almost no variation whatsoever. Any actual story is frequently lost among endless descriptions of, and reactions to, the latest tea-cozy. (Or there about.)

Whatever Jane Austen’s rationale for writing this way, it does not justify the truly painful result. It is physically hurtful to me to read her writing; my brain throbs horribly trying to digest all the trivial minutae of Regency life, told in her boring, exacting, computer-program-like sentences. Jane Austen, I must conclude, is a rather good storyteller, but one with horrible, horrible writing – rather like Herman Melville, in that respect. Hidden beneath her dreadful, tiresome prose are some genuinely wonderful, charming stories, but her writing makes this difficult to appreciate for me. I know some people seem to really enjoy her prose – I am simply not one of them. I’m just not structured that way. It’s a shame, really, because the woman (Austen) was obviously brilliant; a genius, to be sure; and even her horrid writing is still intricate and clever, and certainly required some real brainpower to create – it’s just not very much fun to read. And though I acknowledge her obvious brilliance, I actively despise the effect her writing has on me. It’s become so bad that whenever anyone even MENTIONS actually reading a Jane Austen novel, I reach for my gun…Figuratively speaking, of course.)