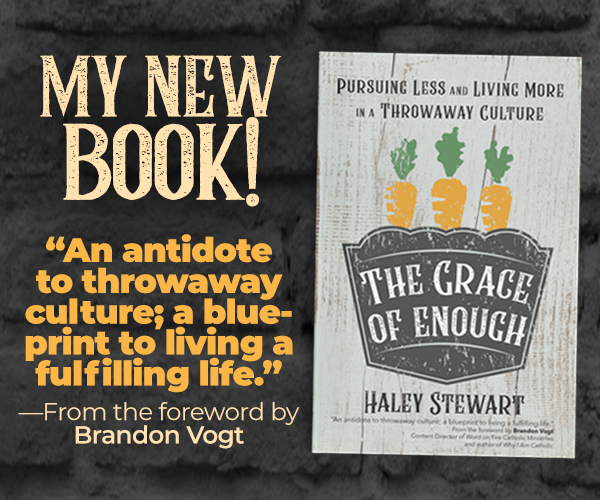

I know it’s been Flannery central over here lately, but Kendra’s post sparked lots of conversations between Daniel and I about why O’Connor is so amazing. Sorry if we’re beating a dead horse here, Kendra! I promise to stop with the “please, love Flannery!” posts. But sometimes Daniel writes things that are just too good not to share. So, I hope y’all enjoy a few thoughts on Flannery O’Connor from the guy with the giant beard.

“Jesus was the only One that ever raised the dead,” The Misfit continued, “and He shouldn’t have done it. He shown everything off balance. If He did what He said, then it’s nothing for you to do but throw away everything and follow Him, and if He didn’t, then it’s nothing for you to do but enjoy the few minutes you got left the best way you can by killing somebody or burning down his house or doing some other meanness to him. No pleasure but meanness,” he said and his voice had become almost a snarl.”

-Flannery O’Connor, “A Good Man is Hard to Find”

I read Kendra’s post and was perplexed by her choice to compare Breaking Bad and Flannery O’Connor. Not just because one is a TV show and the other is an author, but because they’re so different in tone, style, and theme. They’re both violent but that’s like lumping together Jane Austen and Ten Things I Hate About You because they’re both romantic. Besides, the violence in each serves completely different purposes.

In Breaking Bad, the violence is perpetrated by the main characters and serves to drive them deeper and deeper into inhumanity and isolation. I’m sure someone could give a spirited defense of this portrayal of violence. Perhaps something about how “war begets war, violence begets violence” (Pope Francis said that!) and that illustrating this could be beneficial. But I’m not interested in making that defense. I enjoy the show, but I’m certainly not passionate about it.

Flannery O’Connor is another matter, however. She really helped me understand Christianity and the Catholic faith specifically. And more than any theologian, it is Flannery who convinces me to pursue Christ wholeheartedly when my perseverance begins to wane. “He either did or he didn’t,” I tell myself, “And you have to live accordingly.”

Someone might think the violent and grotesque elements of O’Connor’s stories are meant to show the reader that life is brutal so we must be meant for heaven. But I don’t think that’s what O’Connor is trying to do at all. That’s a kind of Gnostic interpretation that misses not only Flannery’s point but also the point of the Gospel. Miss O’Connor’s violence is part of a relentless–at times terrifying–grace that hounds her characters. She shows us the the same violent grace that threw Saul from his horse and blinded him. The same grace that drove the disciples to the ends of the earth where they suffered horrifying deaths. This suffering and violence is not just an unfortunate reality that sometimes confronts Christians, it’s an integral part of what it means to encounter Christ

Perhaps part of the reason we’ve forgotten this is we live in a Christian (or, sadly, post-Christian) culture that is essentially safe. We’re safe from persecution, of course. But, more dangerously for the Christian, we’re safe from a violent encounter with Christ. What I mean by that is that we’ve all heard the bloody, scandalous, disturbing elements of Christianity for so long they’ve lost the ability to shock or surprise. It’s easy to forget how radical the call of Christ truly is. We’re able to wear the ancient Roman symbol of humiliation and death without causing a stir. Quite the opposite, the cross has become a ubiquitous fashion symbol. Most westerners have at least HEARD the idea that Jesus, a human, is also God. So no one is shocked anymore. We can even get away with dulling down Jesus into a rather pleasant teacher who would probably LOVE to chat with Oprah.

But to the people of first century Rome, the story of Jesus and the practice of Christianity was violent, grotesque, and shocking. Pagan sensibilities were scandalized by the idea that God would become man (not just take a human form) and subject himself to all the physical vulgarities of our lives. That God would become a helpless and dirty infant was a disgusting concept to most people. And that this God would become even further degraded by suffering the humiliations of torture and death on a cross was simply unthinkable.

And the scandal didn’t end there. Christ didn’t simply pass through filth and violence to come out on the other side of a clean, spirit life. When Christ rose from the dead, he did so in his physical body! Glorified, yes, but physical nonetheless. Flesh and blood. One of the most moving (and, I think, theologically important) passages of scripture is when the risen Christ cooks breakfast for the disciples on the beach. “It is the Lord!” Peter shouts before plunging into the water. And how does the Lord appear now? A spirit? A godlike body free of the scars of life? Nope. It’s Jesus. The man. His wounds healed but not absent. His stripped back bent over the fire, sweat on his scarred brow, the nail holes still there as he picks out fish bones with greasy hands. This is God. And this is scandal. But it’s nothing compared to the way Christians worshipped their risen Lord.

Hiding in the bone lined catacombs, the bread and wine set out on the tombs of dead saints, the blood of the martyrs on the floor, these Christians literally feasted on their God and drank his blood. This is what we still believe and do. This is why our altars contain relics. And this is what we celebrate when we pray the Anima Christi, asking that the blood of Christ inebriate us. If this sounds scandalous, even disturbing, GOOD! It should. And it did for many centuries. Pagan philosophers wrote vehement polemics against these God-hating, cannibalistic Christians and their disgusting attempt to subvert the ancient social order.

Today, it’s difficult, almost impossible, to convey the scandal of the gospel. If someone were to bravely take up the task of shocking us out of our complacent, easy, and socially acceptable religion, that person would probably need to use something violent or grotesque to get the point across. O’Connor was keenly aware of this. She once wrote, “Writers who see by the light of their Christian faith will have, in these times, the sharpest eye for the grotesque, for the perverse, and for the unacceptable. To the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.” A gunshot is a much more mild form of death than crucifixion but, in “A Good Man is Hard to Find” it shocks our almost-blind culture. A prosthetic leg and a monkey suit are not nearly as absurd as the idea of a God who is at once fully divine and fully human but these elements are just strange enough to grab our attention. Yes, it is shocking when a boy is drowned and baptized at the same time. But that’s what baptism is supposed to be! We’ve been to so many that we’ve forgotten this.

O’Connor’s violence, like much of the violence in scripture, serves to drive her characters closer to their purpose. This makes no sense to our fearful and spoiled culture. But the violence in her stories is at the service of grace. Some people read O’Connor and are shocked and horrified. But this isn’t a bad thing. If we’re shocked, it’s probably a good thing. Because we may then be able to understand the shocking nature of the Jesus story and what it must mean for our lives.

Flannery’s stories may not have typical, fairytale endings. But neither do the stories in the New Testament. Christ doesn’t call us to earthly happiness, he calls us to suffering and death and resurrection. He calls us to join him in his triumph. The path there can be joyful but not always neat or pleasant. As Jesus said, “The kingdom of heaven suffereth violence, and the violent bear it away.”

Bravo, Daniel. It is crucial to be challenged and to be made uncomfortable, but we actively avert from that, because those things are just that – uncomfortable. A sincere thank-you to both you and Haley for your beautiful insight.

This is just beautiful Daniel. Thank you for writing it. I could not agree more with every word you wrote about the truth of how God chose to redeem us. I love that gnawing in the gut feeling it gives me. And the wonder and humility and hope that it inspires in me.

But, for this particular reader, that’s what’s missing in Flannery O’Connor. I know it’s there for you any many others. But it isn’t there for me. Although Breaking Bad and Flannery O’Connor are so very different in scope and purpose and presentation, they both leave me with a feeling of hopelessness and despair. I don’t know about the intentions of the creators of Breaking Bad, but I am certain that that wasn’t Miss O’Connor’s intent. But still, there you have it.

I have read and studied her works in some depth, and still feel like they are not the best path to holiness for me. I’m willing to give her another try sometime down the line, but for now, I’m comfortable saying: This doesn’t help me personally to be a better Christian. And that wasn’t an opinion I had ever heard from other faithful, studious Catholics. So I wrote about it on my blog.

There are so many different ways to get to Heaven, I’m glad you and Haley and out there fighting the good fight for Flannery O’Connor, but I think for now we’ll just have to be content with both loving Kristin Lavransdatter. And that’s something, right?

Is it ever! Daniel’s reading Kristin for the first time and so are my dad and brother. Talking about it with them is making me realize I desperately need to read it a third time ASAP. Thanks for being a good sport, Kendra, while we jabber on about Flannery 😉

Okay, I’ve been spending an embarrassing amount of time contemplating this….or perhaps more accurately, stewing over it 🙂

I think the comparison of Breaking Bad and O’Connor in the original post by Kendra (and please forgive me if I’m mistaken!) had less to do with the purpose or worthwile-ness of the violence in both and more to do with the idea that both are things that all the cool Catholics are watching/reading that leave some of us feeling icky and like we would rather not watch/read them–and that that is a completely acceptable position for any (aspiring) cool Catholic to take.

For years my own dislike of reading O’Connor has been my secret shame because every time she came up it seemed like there was this condescension towards anyone who didn’t like her as “just not getting it” and as an educated (okay, and prideful) Catholic I don’t like to be seen as “not getting” something. I really appreciated Kendra giving ‘faithful, studious Catholics’ like me permission to say out loud “meh” when discussing O’Connor. And I fully realize that it’s sad that I felt like I needed permission to not like an author 🙂

Saying “this doesn’t help me personally to be a better Christian” perfectly sums up how I feel. I’m not sure why reading O’Connor leaves me despairing but it does. Maybe the fact that I have had real suffering in my life and actual experiences with fear/guns/police/death/etc makes me too sensitive to those themes to enjoy reading about them? Maybe reading O’Connor doesn’t shock me out of complacency, but rather shocks me back into those memories and (while I’m sure it’s worthwhile and edifying for others) for me it’s not a productive shocking?

When you said “a gunshot is a much more mild form of death than crucifixion but, in “A Good Man is Hard to Find” it shocks our almost-blind culture” it reminded me of Chesterton’s character Innocent Smith in ‘Manalive’ going around with his own pistol shocking the people he meets out of their complacency–that kind of shocking I can handle. I think for now I’ll be sticking with Chesterton because I feel like reading him does make me a better Christian. And of course Sigrid Undset, I can definitely agree with you all on her 🙂

PS I don’t mean to make my life sound chaotic, I just had a bit of a dramatic childhood

Hi, Kendra. This is Daniel. Thanks for putting up with us! I understand the feeling of not liking things everyone thinks you should like. And, of course, there must be room for simple preference.

I’ll also say that many southern writers can be difficult for non-southerners. I think there’s something that goes beyond the unique culture and dialects. I’m thinking of Faulkner here. Both he and O’Connor have a dark humor that I really enjoy but I can see others finding horrifying. At our age, who’s got time to read something they simply don’t like?

Also, as a southerner with a family history more disturbing than anything O’Connor or Faulkner ever wrote, the idea of despair never really enters my mind. But that’s another story. Anyway, thanks again.

A well-composed, thoughtful, insightful commentary. F.O.C. would be proud.

Thank yoU!

Haley, I appreciate so much your take on Flanner O’Connor, and how important an author she is . I’ve appreciated her work for a long time, although, the last time I read her (years ago), I was Christian, but not Catholic. Your perspective here is wonderful, and I thank you for putting it so very eloquently into words for us.

Oh now this was just too good. Thank you for writing!

Oh my gosh, Long Beard Man- I am not kidding even a little when I say that your essay on O’Connor completely unpacked her for me, and for the first time I feel like she may be accessible.

I remember reading “A Good Man is Hard to Find” and the one about the boy who drowns himself and coming away thinking, “Urgh. I hate it when I’m too stupid to understand a story!” Now, I think that lots of times, because I am a stupid person. From time to time, I stumble across someone who will help me unlock the meaning, and usually I come away thinking, “That’s IT? THAT was the big symbolic point?” but not this time.

This time, I feel like I’m ready to go be re-scandalized by the Gospel, the better to take it to heart. And if a man in a gorilla suit is what it takes, then I’m ready to hear it.

Thanks for laying it out clearly and enthusiastically for ding-dongs like me.

SO. GOOD.

I definitely agree that Flannery brings life to the more bizarre, ugly, and violent in order to show how grace can coexist with it and triumph over it. The problem arises that our culture is so sanitized. We have such a little grasp of real violence, the violence of the battle for our souls.

But, so well written….love!

Big Bearded Man, somehow your posts always say exactly what I need to hear. I don’t really have a comment on Flannery O’Connor (haven’t gotten to reading her stuff yet), but I love everything you said about the violent, scandalous nature of the gospels, and the truth of what we believe. I hope you don’t mind if I share some of your words with my catechism students later this year.

~Willow

“it’s an integral part of what it means to encounter Christ”

YES. I’ve been curious to read Flannery O’Conner and was disappointed when I read Kendra’s post– only because SO SO SO many people quote her and write about her! I figured her writing style to maybe be Chestertonian? Wrong wrong wrong, was I apparently.

But what you’ve written is exactly what Christian Peace is– how it’s misinterpreted to be this thing of rest and comfort isn’t quite it!

I just listened to this 2 minute audio this week that had me connecting Christianity with this strange melange of “violent peace” and it unsettled me greatly. Shocking, Christianity is.

I hope you don’t mind me sharing– it’s two minutes of audio from St. Luke Productions:

http://www.stlukeproductions.com/benedictus-media/mp3/09_13.mp3

Yes, yes yes. I love O’Conner for this exact reason.

My favorite lit prof in college called it “using your religious imagination” when we would find grace propelling O’Conner’s violence. There’s no cut and dry reason why a murder of a two year old should contain grace, but it does, at least in O’Conner’s stories. Maybe all of us are just really crazies when we find grace blazing in murders and misfits, but I think it’s just because we recognize that God doesn’t play fair.

And thank God (literally) that he doesn’t, because without that battering of our hearts (mixing metaphors and authors alarmingly here, but it’s fun to pretend like I’m back in college) we’d just stay in our self-satisfied blindness.

Thank you for this beautiful post, Daniel. I hope you don’t mind, but I think I will be sharing it on my own blog. Flannery has been a light to me as well.

I think she is one of the many uncanonized saints.

Do you have any thoughts on the new book of her personal prayers that is going to be published? I cannot help but feel slightly uncomfortable that writings so personal and intimate will be on display for the world — and I cannot help but feeling that Flannery herself might have a thing or two to say about it.

Although I suppose the Beatific Vision might change her view of things, even her own private prayers.

Thoughts?

Maura

Thank you so much for writing this. Sometimes I have trouble explaining just what it is about Flannery that I love so much and I think your post hit the nail on the head.

One thing to contribute, the best introduction to her writing that I’ve ever come across was by Fr. Barron in his book “And Now I See”. He has a whole chapter where he unpacks “A Good Man is Hard to Find” and explains the workings of grace in the story. Usually when I recommend a friend to read her stories, I direct them first to a bookstore so they can read that chapter (most can’t afford a $30 book just to read one chapter). It helps them to understand how to approach her stories so they’re not just shocked by her violence and leave with a bad taste in their mouths.

Anyways, thanks for doing what you’re doing. I love your taste in literature.