Welcome to Carrots! I'm so glad you're here. This is where I share thoughts on liturgical living, faith, parenting, culture, and an extra dose of Jane Austen. You can sign up for my email newsletter here to stay in touch, or look me up on Instagram!

I’m re-reading Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park for the fourth time as part of an online book club. As we make our way through the book, I’m hearing all the comments I expected to hear about the book: “This is my least favorite Austen novel.” “Fanny just isn’t likable.” “Why is she so boring and prudish?” “Mary Crawford would make a much better heroine.” “Lighten up, Fanny.”

And those reactions are so understandable. Mansfield Park is hard to love. There’s no getting around that. The heroine, Fanny Price, is painfully shy, serious, and introverted. Elizabeth Bennet she is not! She doesn’t sparkle across the pages with witty banter (that’s Mary Crawford’s job). And she isn’t transformed throughout the course of the book like Emma Woodhouse or Marianne Dashwood. Fanny of Chapter 1 is very much the Fanny of the final page. She’s hard to identify with and her strong moral convictions often makes her come across as a killjoy.

What is Austen up to? I think she intentionally makes Fanny difficult to fall in love with. I think she planned for us to like the Crawfords best for most of the novel. Even though I know how it all turns out, when I get to the point when Henry appears to be reformed, I always find myself rooting for him to win Fanny. He’s so charming! But why would Jane Austen make it so hard for us to love the right characters?

In A Jane Austen Education, William Deresiewicz claims that Austen’s main theme in MP is money and how it corrupts. He notes how the Crawfords both are skilled at playing a part–being charmers, being pleasant, knowing how to act to win someone over. But he explains their depravity with the boredom that comes with wealth: needing to be entertained and to always entertain others. He seems to miss the idea that it’s their moral education (and the Bertram siblings’ moral education) not their place in society that failed them. Without embracing Austen’s moral philosophy, Mansfield Park will always be misunderstood. Perhaps that’s why every film adaption of the novel seems to get it wrong.

Austen is masterful and complicated, so I’m not saying that themes of wealth and critiques of the aristocracy aren’t present in the novel. They are, and Deresiewicz is right to point them out. But I think Deresiewicz completely missed the main point. Mansfield Park is about superficiality versus substance. It’s about charm versus goodness. It’s about mere conventional propriety versus true virtue and it’s hard for an entertainment-obsessed culture that glorifies appearances and laughs at the idea of character to understand. All of the characters struggle and are tried and tested…but some fight the good fight and others reveal that they never had virtue to begin with.

Let’s talk about Mary Crawford. Oh, Mary. She’s beautiful and funny and witty. She pokes fun at herself and other people. And sometimes she’s even thoughtful (when it makes her look good). But it’s clear by the end of the novel to the romantic hero of the story, Edmund, that she’s actually a selfish vicious woman who’s simply very skilled at making people like her. It’s like that scene in High Fidelity with John Cusack when he attends a dinner party at an ex-girlfriend’s house. He’s always been under the spell of this beautiful, cultured, witty, and sparkling woman named Charlie. But listening to her conversations after not seeing her for several years, he realizes that’s it’s all a big show. She can manipulative people into liking her…but she has no substance. She’s just a petty, catty woman who wants to feel good about herself. In his character Rob Gordon’s words, “And then it dawns on me…..Charlie’s awful.”

Edmund, all of the Bertrams, and we, the readers, are taken in by Mary. She’s so fun! She’s incredibly perceptive. She’s enchanting. It takes most of the novel for him (and us) to get there, but finally it dawns on Edmund: Mary’s awful. Everything she does is to promote her own interests. She does nice things when someone who matters is watching. She is so skilled at charming people that she probably even has herself convinced that she’s a kind person.

Fanny sees through her from the very beginning. It’s not that everything she does is vicious or cruel, but she’s only kind so that other people will like her, not kind out of genuine concern for them, not because she cares for them for their own sake. I can identify with Mary. I’m a people pleaser. I desperately want to be liked and I’m pretty good at getting people to like me. But if I’m not careful, that can become my all-consuming purpose. It’s an inner struggle to put virtue and genuine care for other people ahead of my desire to please, but Austen shows me what a monster I might become if I don’t keep fighting that battle within myself.

And then there’s Henry Crawford. Easy to hate at the beginning, and hard to deny when he seems to be reformed from his life of selfishness and vice and truly in love with Fanny. Yet, Fanny’s moral intuition is right again. Henry Crawford’s vanity and selfishness isn’t merely a personal flaw that affects his own soul and his own prospects for a happy union with Fanny. His obsession with being liked by everyone, or as Mary puts it, needing to “have a somebody” at all times, destroys his sister’s marital prospects, the Rushworth’s marriage, and the Bertram family’s reputation. Every sin is a sin against our community. No matter how secret we’d like them to be, our vices hurt people and we don’t like to be reminded of that. Austen illustrates that truth for us in Henry and Maria’s foolish affair.

Mary’s claim that if only Maria had cheated on her husband with Henry without being detected, all would have been well, shows Edmund that she has no sense of the moral evil of their actions. Edmund is devastated by the crime itself, not merely that Maria and Henry’s affair has elicited a public scandal. Edmund notes that if only Mary had been given a good foundation in virtue, what a wonderful woman she would have been! Austen realizes how vital a good moral education is in order to develop virtue.

The Bertram girls, Maria and Julia had a more complex problem than Mary and Henry’s very obvious lack of moral education. They seemed to understand what it meant to have character, but really they only learned how to behave. They may have been elegant ladies but they had no sense of the gravity of marriage, faithfulness, and virtue. It was all superficial, all external. They could enter a room with an air of grace, but they had been taught (by their selfish Aunt Norris) to think of themselves first and others as an afterthought.

And then there’s our quiet, shy, and unlikely heroine. Fanny is kind, thoughtful, smart, and passionate. She’s a devoted friend and a good listener. Although she isn’t taken in by charm, she wants to believe the best of people and treats everyone with respect, whether they deserve it or not. So why don’t we like her?

First of all, I think we’re not used to introverted heroines. A shy, soft-spoken heroine is both unexpected and dissatisfying. And as a culture, we want to be perpetually entertained (just like the Crawfords….yikes). This is more true now than when Mansfield Park was published. Fanny isn’t the sort of “strong heroine” we like to extol. What we really mean when we say “strong” is “outgoing,” like Elizabeth Bennet. But even though Fanny isn’t an extrovert, she is indeed strong. With a painfully shy temperament that dearly longs to please those she loves, she has the strength to stand up for what she believes to be right even when everyone (including Edmund) is participating. Even when she’s ridiculed for it. Edmund looks like a spineless whelp compared to Fanny with her unshakeable moral fiber and devotion.

Developing a friendship with Fanny is slow going for the reader, but it’s worth it. She’s like the quiet girl in class that you didn’t talk to until halfway through the year and then turns out to be your new best friend. She’s the friend you can talk to for hours and who really listens. She remembers to call on your birthday and brings over a meal when there’s a crisis. Fanny knows that charming people only care about how others perceive them, not about what’s really inside.

By the end of the book, at least after the second reading of the novel, I hope you like Fanny. Because I think that Austen is slowly and surely bringing us along to have better vision of the worth of others and our own obsession with being liked. In some ways, Mansfield Park could also be understood as Austen’s indictment of herself. Every bit as clever as Elizabeth Bennet, Austen surely had the capability to mask pride or selfishness with wit and charm anyone she desired to charm. But as Elizabeth learns in Pride and Prejudice, a sharp tongue isn’t a virtue, even if it makes you entertaining. Austen surely knew this as well, and perhaps that’s why she created a character without wit and with true virtue. Fanny Price might be nearly impossible for our culture to understand, but that’s why we need her more than ever.

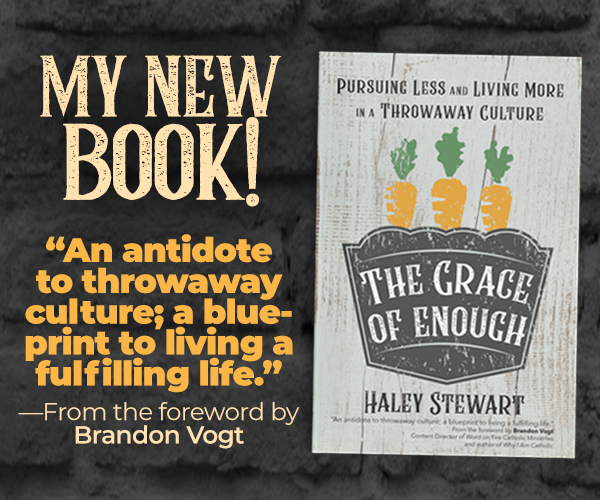

Haley,

You are 100% right on all of this (especially the moral education), but I STILL don’t like Fanny. What ever will you do with me?

I guess I should clarify, I think I would love Fanny in real life. How could I not? She’s thoughtful and helpful, and even if she disagreed with me, she’d mostly just keep it to herself.

But I find her inner dialog to be wearying. Extraordinarily wearying. Maybe that’s why she’s so quiet. So mostly people don’t have to be exhausted by her fretting. I’m exhausted.

I like Mansfield Park least of all of Jane Austen’s books because there isn’t a single character I identify with. It’s got my least favorite hero and my least favorite heroine. But I’ve still read it multiple times because even my least favorite Jane Austen is still Jane Austen.

Haha! I think a lot of this has to do with her introversion. It is loud in her head even though she doesn’t speak much and we’re privy to everything going on in there. I am with you on Edmund being the worse hero. I dislike him more every time I read MP. Why does Fanny even like him? He seems easily manipulated, hypocritical, AND not any fun. Fanny may not be the life of the party, but she’s good as gold and he doesn’t deserve her.

Yes. I just wish Henry could’ve been allowed to keep it together like Anna suggests. It seems like a much happier ending for Fanny to end up with someone who loved and cherished and pursued her and reformed himself for her. I think her could have been a better compliment to her than Edmund, who was disappointed in Mary, but still seemed to pine for her a bit, and looked around and there was Fanny, so her married her.

Yes, this! I love Fanny to bits, but I cannot stand Edmund. I always end the book disappointed, because I can’t see their marriage going well. I feel like he would end up wearing her down in the end, rather than cherishing her as he ought.

Completely agree with you. I hate Edmund as much as I love Fanny.

I don’t agree. Bertram was Fanny’s first friend, and she loves him for good reason. “With all the gentleness of an excellent nature” he eased her homesickness by taking the time to find out what would most help her (writing to William), guided her education, and advocated for her at every turn (even when it was unpopular with others). He gave up one of his own horses to trade for a suitable mount when “Fanny must have a horse.” Yes, he fell for Mary Crawford, but so did everyone else. He is ever attentive, always values her intellect, and is morally sound. I think he will be an excellent husband and I would enjoy having him for my pastor.

I think what bothers me about Mansfield Park (which, in truth, I’ve only read once) is that Henry and Maria’s affair seemed to me to be very sudden and out of the blue, like an afterthought. Almost as if Austen realized she’d made Henry too likable and had to force Fanny back with Edmund. There just didn’t seem to be any motivation for the indiscretion, since Henry was making good headway with Fannie–he didn’t need Maria’s attention. And, I desperately wanted their to be some moral development in the story–you’re right, Fanny doesn’t grow and change, and she really could stand to become a little less anxious. No one in the story has any sort of normal human growth, and I really wished that Henry had been allowed to really reform. He would’ve made a much nicer hero, and his reform would’ve shown that even rich/bored people are not excluded from the Kingdom, even if it’s hard for them to enter. I found his eventual fall not only surprising and unbelievable, but also kind of depressing and fatalistic.

But, I do admit that I might be wholly too influenced by Alessandro Nivolo, the handsome actor who played Henry in the (very inaccurate) recent-ish movie adaptation

I am always a bit swept off my feet by Henry Crawford. And who doesn’t want the reformed bad boy that every girl wants to fall in love with you? But I don’t think the affair was surprising. The motivation Henry needed was simply that Mrs. Rushworth wasn’t giving him the time of day and he wanted to be liked. For someone as selfish and vain as Henry, it doesn’t matter that he’s supposed to be wrapped up in an actually worthy woman, he needs EVERYONE to love him, even if he doesn’t care two cents about the woman. So he does need Maria’s attention. He shouldn’t need it. But he does. He wasn’t doomed to be that sort of man, but by making small steps toward his former life, he slipped back into his vice. First he was just going to see the Rushworths. Then he was just going to flirt a little….it’s the same guy who wanted to entertain himself by making a “small hole in Fanny Price’s heart.” It wouldn’t matter whether they had gotten married or not, Fanny wouldn’t have been enough unless he learned to stop being selfish and vain.

And I think the moral development in MP is really in Edmund and Sir Thomas. They both learn to have some real vision.

But I agree that getting together with Edmund isn’t a very satisfying end :/

Hi.

I would dare mention at this point that the very simple fact that Henry Crawford even thought it was appropriate to visit Maria Rushworth in the house of her husband speaks very clearly of his lack of understanding regarding the moral meanings, implications and consequences of his actions.

He had already disrespected a social and moral taboo by offering his attentions to two ladies at the same time.

At that time in history, a gentleman was required to be very careful with how much romantic attention he pays to a lady and very importantly, how openly he does that at different stages of the relationship. Being too obvious before he made his serious intentions clear to the father of the lady (or whoever else in charge legally) would have exposed the lady to the society’s gossip. If the lady, usually young, inexperienced and impressionable, were to have answered to his attentions publicly before the official explicit marriage proposal was accepted, that would have exposed her even more and ruined her reputation as a decent lady of proper conduct.

So, even going too far, too fast with only one lady would have been wrong. Enamoring two ladies at the same time was even worse. Directing his attacks against an already engaged lady was, again, even even worse. Doing that to two sisters, pitting them one against the other and possibly causing scandal in their family, AND thus exposing the entire “game” even more openly, was even even even worse.

As if that alone hadn’t been more than enough, he has no problem in pushing the disrespect even further – make himself a guest in the house of the offended fiance – now husband. It wasn’t enough that he flirted with his fiancee in her father’s home, under the fiance’s nose – now he felt the need to flaunt himself under the wife’s wounded, starving and oversized ego, in THE HUSBAND’s home. With what other intention if not to satisfy his own ego by renewing the flirt? With what other mentality except the total lack of respect for decency, propriety and for poor Mr. Rushworth – the future cheated and dishonored husband?

To do what he did at Mansfield Park, in those times in history, enamoring the two Bertram sisters at the same time, one of which already engaged, with all the risks for their reputation deriving from this, showed clearly how much and how profoundly he lacked thee needed moral principles. Such a deep and fundamental lack of morals can’t be overcome or at least partially replenished at his age, not even by the love of an …. angel…, much less by the love of any human being, not even one as sweet and virtuous as Fanny. What he did later, in Mr Rushworth’s home, only confirmed the extent of his moral issues – how much he lacked the necessary moral principles.

As for Edmund, he was a very lucky fellow that Fanny had such a sweet and tolerant disposition and that she loved him so much, so steadfastly, even when he didn’t even know she existed romantically speaking, after he declared Mary C. to be the only woman for him to have as a wife. From the book, I felt like he just accepted what was easily and practically unconditionally available within his reach, while very well known and unlikely to produce any unpleasant surprises in the future.

As for Fanny in the book, I never would have imagined she was so little liked – she’s a wonderful character in all the important aspects. I understand she is not well liked because of her introvertedness and because of her too reserved, shy and moralizing nature. Her unwavering morals are what make her worthy of being the leading character in this book. Her shy and reserved nature is due to her natural personality AND to the way she was treated and reminded, in everything, that she is always supposed to be “the lowest and the last”. However, even if she is pushed into that attitude by her nature, coupled with the treatment she endured and with the social expectations of those times regarding a young girl and a poor relative surviving on the charity of the rich, even so, she still shows a few glimpses of a more sharp judgement – when she takes initiative with the silver knife, the first time she has the slightest amount of financial independence to make a decision of her own; also after she receives that letter from Edmund, in which he tells her that he has delayed the moment to propose to Mary C. – she has that dialogue with herself – disappointed, even angry at Edmund – “let him talk to her … he will be unhappy with her; … he doesn’t even see it … but let him do this and be done with the uncertainties … !!!” – maybe not these exact words, but with this meaning. I think she shows here a little more than just extreme shyness and “prudishness”(which I personally never saw in her) – her opinions look no longer rigidly inert in their unwavering morality (in reality they never were RIGIDLY INERT- there was always a valid reason for not wavering) , now there’s also quite a lot of sharpness of judgement, unexpectedly a lot.

I personally like Fanny Price very much.

Love the discussions.

Fanny is also modeled a the kind of heroine that we don’t recognize, because she disappeared after the 18th century. I didn’t like Fanny until I tried to read “Pamela, or Virtue” – my theory is that this is Austen’s take on what WAS well-established genre. Richardson wrote Pamela, and the heroines of those novels were always perfect. Always. Stuff happens TO them, and they never have agency. Austen and her predecessors Fanny Burney and to some extent Mary Wollstonecraft popularized the plot actually driven by a female character, and then we have George Elliott and the Bronte sisters to thank for continuing that tradition. The point is that Austen melds genres in a way that we don’t recognize but in a way that was really the work of a pro–you have to know your stuff to play around with the rules by allowing us to feel frustrated with Fanny and to like Mary Crawford. According the rules of the 18th century novel, we should love Fanny, always, and hate Mary, always.

That’s fascinating, Anne-Marie!

Yes!!! Someone who understands. I’m with you 100%. Fanny is actually one of my favorite Austen heroines, because of her personality. I identify with her a lot. I greatly dislike societies glorification of the extrovert. I believe if more people would be quiet reflectors and listeners, our world would be a better place. Another reason Fanny is sorely needed today, is because the popular novels with heroines that are quiet & introverted are worrying. They usually end with the heroine becoming a vampire, witch, or other supernatural thing.

Great post! Another reason why I think we’d be friends in real life. Fanny has always been my second favorite Austen female.

I haven’t read MP, but this makes me want to. I am painfully introverted myself and haven’t seen introverted heroines much.

Haley, I don’t think that there are words to express to you how much I LOVED reading this post!!!! It was amazing and spot on perfection! Mansfield Park is my favorite Jane Austen book. I adore Pride and Prejudice but I have always had more of a connection with the Fanny Price’s and Anne Elliot’s of this world more so than with the Emma Woodhouse’s or Eliza Bennett’s. Thanks for this post and I’m sharing on my Facebook page! ~ Jamie

“The heroine, Fanny Price, is painfully shy, serious, and introverted…She’s hard to identify with and her strong moral convictions often makes her come across as a killjoy.”

Haha! This could be a description of me! I guess that’s why I didn’t have any problems liking Fanny: she was easier for me to identify with than Elizabeth Bennett (whom I still liked) or Emma (whom I found to be very annoying).

I’ve only read Mansfield Park once, but now I’m thinking another read through might be called for.

Hear, hear! I just read Mansfield Park for the first time, and I agree 100%. Though I admit at times I wanted to look Fanny in the eye and say, “Relax. Breathe. It’s oooookaay,” I disliked Mary almost from the start. Every time she spoke I just wanted to smack her. But that may be due to growing up painfully shy myself (though less anxious than Fanny, thank goodness) and knowing EXACTLTY the sort of semi-kind, patronizing, isn’t-she-cute-in-a-pathetic-way, aren’t-I-a-nice-person-for-talking-to-her smirk that was on popular-girl Mary’s face when she interacted with Fanny.

I wondered how Austen would make Edmund change his mind and like Fanny instead, and I kind of didn’t think it was going to be believable, so I was glad in a way that she did it as vaguely as possible and left the specifics up to our imaginations.

(Though, like you, I did find myself sort of rooting for Henry against my own better judgement.)

I was wondering why everyone was getting down on Fanny! She and Anne have always been my favorites but I never really thought about why when it’s obviously because we have similar personalities (including the anxious inner dialogue). But I feel sorry for poor Edmund, all of them are so young and he’s just trying to find his moral center with nothing to go on because all of his role-models are wrong. The fact that he figures out that it’s Fanny is really amazing because he has to see through and reject every other character’s opinion of Fanny in order to see her for the person that she is. In fact he IS the reformed “bad boy” who has been saved by choosing Fanny it just doesn’t seem that way because he was always trying to be good (and getting it wrong). In my mind he chooses Fanny as a bit of an afterthought and then thanks his lucky stars for the rest of his life as he grows in the understanding of her true value, we can only hope

Masfield Park is been my favorite Jane Austen novel! I think it’s because I identify so strongly with Fanny. I’m introverted and shy and have often felt like distancing myself from my group of “friends” because they were doing something that I didn’t feel was a good idea (just like the Bertrams, etc. putting on that play). I also identify better with Jane than Elizabeth Bennet – probably for the same reason!

And I’m really upset that all the movie renditions of Mansfield Park are simply awful. Ugh.

Have you tried the 1983 BBC version of Mansfield Park? Of the lot, I think that one comes the closest to capturing the book. It’s on Netflix.

I haven’t! But you’re the second person to recommend it! I will netflix it one morning when Baby Gwen wakes extra early and we have a couple of hours before the big kids get up

Love your insights, Haley! But I never found Fanny nearly as difficult to stomach as Emma or, heaven help us, Catherine. Fanny does not make me cringe, as those two tend to do.

[Am I the only one who occasionally talks out loud to characters, ” What are you THINKING?!” ?]

I always liked Fanny the best out of all of the heroines but I’m pretty sure that’s because I’m a major introvert and worrier. I identify a lot with the character and there is so much to learn from her! This is a great post on the subject and I very much enjoyed reading it.

(I also liked your thoughts on Fanny being like the shy girl in class you don’t get to know until halfway through! I have seen that kind of thing from both sides. Both in being that girl and knowing that girl. Now that girl truly is my best friend!)

I completely agree with you, Haley. Fanny is so strong, but her strength is in her moral conviction, not in public speaking or persuading. But Mansfield Park is still my least favorite Austen novel, and I think it’s because of Edmund, not Fanny. You said it perfectly—Edmund is a spineless whelp compared to Fanny, so I always felt he didn’t deserve her and wasn’t her moral and intellectual equal. I suppose I can forgive him for being drawn in by Mary in the beginning (even though I don’t want to . . .), but I can’t forgive him for talking to long to appreciate Fanny completely. I always felt that his attitude in the end is like “Well, Mary was a bust . . . Hey, that Fanny isn’t too bad looking . . .” He always seemed rather shallow to me, even if he’s nice and gentle. He’s the one Austen hero who doesn’t deserve his heroine, in my opinion. Even Edward Ferras, who is kind of unforgivably dopey and shy at times, sees the error of his ways in choosing Lucy Steele even before the novel begins and attempts to mend his ways.

What do you think?

I completely agree! Edward is my second least favorite hero, too.

*too long. Sorry!

Oooh, now you make me want to read Mansfield Park. Is there ever enough time in the day to read?

saving this for when I finish– I got started late in the bookclub!

Haley, I can’t tell you how much I love this post! I read Mansfield Park about a year ago, on the recommendation of my housemate at the time, a dear friend who is getting her PhD in English literature and specializes in the Austen era. She told me no one should get married without reading it, and she also said Mansfield Park is her favorite Austen novel—which makes sense since she is actually very similar to Fanny in personality. Anyway, I read it and loved it! The moral issues and dilemmas at times seem almost quaint to modern readers (nowadays, who would ever have moral objections to acting in a play?) and I was definitely taken in by Henry Crawford and disappointed when Fanny rejected him—but ohhhh man, does she ever get proved right! There is just so much to love about this book. It’s one of my favorites now. And I completely agree that it’s precisely because this book is so outside the norm for what we as modern readers expect that we need to read it and pay attention to what it has to say. Thanks for spreading the “good news” about the awesomeness of Mansfield Park.

My New Year’s resolution (um, hello almost April) was to get into more fiction. I’ve got my eye on your reviews

Haley,

Great post. I found you through the Catholic Bloggers page over on Facebook. I look forward to seeing more of your posts.

I applaud your excellent post on Fanny Price! I have always loved Mansfield Park, and re-read it every year usually around the holidays. She is by far the most uncelebrated of Austen’s characters, so I appreciate your post and pictures.

I think you guys are being a bit harsh on Edward and Edmund. Austen is never advocating for love-at-first-sight-swept-off-your-feet kind of love: the only justification Eliza Bennet ever gives for growing to love Darcy is the joke about loving Pemberley! But more strikingly, there is Marianne, who eventually recognises the worth of Colonel Brandon, but in comparison to her genuine love for Willoughby, it may appear a rather tepid attachment. And yet, she understands his character as better foundation for married life than Willoughby ever could be, and founds her future life on esteem rather than transports of passion. Edward and Edmund are simply the hero version of the same concept.

I think we resent Edward and Edmund because they do not portray the typical kind of perfect, unquestioning love we want for the heroins (and ourselves, identifying with them). There is this idea that coming second is somehow demeaning to the heroins, when, really, there is no reason why the heroes’ love should be less strong, simply because they attached themselves to the wrong woman first. It happens. And if anything, Austen wanted to write about things which do happen. She is definitely not a romantic.

Having not read through all the comments, I’d like to add a thought, my apologizes if it is redundent.

In the beginning, when Fanny first arrived at Mansfield Park, Edmund was the only person to befriend young Fanny. He took the time to listen and get to know her, as children do.

So, possibly, there is a connecting thread through all the years between when Fanny arrived and the conclusion of the novel.

Just a thought to add to the discussion.

Anne

Yes, Anne, i was just reading through these comments and thinking about how Edmund taught Fanny using great works of literature when she was young. It seems to me that he was a better teacher than a student of virtue. i suspect that through their married years, Fanny will be the one teaching Edmund life’s virtues. A very interesting flip of teacher/student relationship.

Manfield Park is the only Austen novel I never finished. I got about halfway through – twice – and just couldn’t bring myself to finish it! I would totally be saying the same things as the women in your book group! But after reading your post….maybe I’ll try to give it a third chance

I’m one of those weird folks who really liked this novel and the heroine! … but I will fully admit that it’s in large part because I read it while traveling in England in 1996 with my parents and grandma. We were staying in a charming hotel in the Lake District and the room had a little teakettle. Best of all, the town of Grasmere had this famous gingerbread shop. I bought a package and took it back to the room and ate it while reading. To this day, I think of Mansfield Park and I taste tea and gingerbread. Good memories.

Okay, nostalgia trip over.

I like what you say about Fanny being an introvert. Introverted heroines are probably kind of hard to make compelling if you are not writing in the first person. But there is something very appealing in the quiet un-flashiness of Fanny, especially in such a loud, flashy world like the one we live in.

I think Fanny Price is the precursor to Anne Elliot. They are both introverted, with intense yet completely concealed emotions. Both are exceptionally good and kind to their family members who absolutely don’t deserve them, and both so completely taken for granted. Both have constant, seemingly hopeless loves for years before sudden victory. I do think Anne is the better character. Fanny is the goodest, but Anne is more interesting to read because she actually grows and learns and becomes stronger as a person, which is key to her finally winning back Captain Wentworth. Persuasion will always be my favorite.

I’m so happy to see an article praising Fanny Price and Mansfield Park! After reading Pride & Prejudice and Sense & Sensibility to my daughter I decided to read & re-read all things Jane. I had never read Mansfield Park and after seeing all the negative reviews I kept waiting to dislike the character and the book. Instead, I found myself identifying with Fanny Price and disliking the Crawfords. Fanny Price is a role model for virtuous Catholic girls everywhere! True love comes to those who wait. Good girls really DO win! I find Fanny a refreshing antidote to all things superficial and “modern”. The world today praises first impressions and quick sounds bites . … but it takes more than 140 characters to appreciate Fanny Price!

I also identified with Fanny Price–I love her! And it’s difficult for me to believe that Edmund actually cares for Mary Crawford for so long without seeing right through her. Mansfield Park is probably my favorite Austen novel.

Mansfield Park is probably my favorite Austen novel.

Very insightful post! I must confess, Mansfield Park is also my least favourite Austen novel, mainly because Fanny’s neglect is never really resolved. I can’t help but wonder for the health of Fanny and Edmund’s marriage if she never speaks up when she needs something and he rarely notices when her needs aren’t being met and then forgets to follow through. Will Fanny ever work up the gumption to ask for a fire in her room? Will Edmund notice his wife’s dresses are ragged at the edges and see that she gets new ones? Will he remember to check if she ever got that horse? Seeing Fanny as an introvert as well as the poor relation explains her unwillingness to stand up for herself, and Edmund’s lack of good examples explains his inconstant attention, but it doesn’t make it fun to read. Especially when you add the cousin lovin’. Unlike the movies, Austen never lets you forget that part.

No way! Fanny loves Edmund because he was always kind to her since she arrived. He notices when she is tired, harassed, unwell, etc. He educates her and lent her a horse to ride, gave her a necklace so she can wear her brother’s present, etc. You need to re-read the book.

Mary Crawford is Elizabeth Bennet gone bad. That’s what I’ve always loved about Mansfield Park. Austen shows us that, despite how charming Lizzie is, without virtue a character like hers is not only unlovable — she’s dangerous. As was noted, Austen is always probing the divergence between style and substance. Lizzie and Emma happen to have both. But if you have to choose, you definitely want the moral fiber. In MP, we readers have to choose between a protagonist who is all substance and almost no style versus a lady who is all style and zero substance. The great thing is that the substantial character not only gets the guy, she is desired by even more! Austen wants us to believe that there is something innately attractive about substance even without the charm. You won me over, Jane!

How I managed to graduate with a degree in English, and not read this – beyond me, especially when I dotted on Ms. Austen’s work! However, was excited (very excited actually) to find it on Kindle for only .99 … and as soon as my busy life gives me the time, this is TOTALLY MOVING to the top of my reading list. YOU have me absolutely intrigued!!

Having not gotten around to reading Mansfield yet, I don’t feel qualified to comment on it, but I can’t help noticing that all you have said about Fanny could be compared to the Virgin Mary! Shy, introverted, didn’t speak much but had a sensitive heart that was prone to anxiety (losing Jesus when He was twelve brought that out into the open… also Simeon’s prophecy that her own heart would be pierced by all that happened to her Son); not to mention the strong virtue and moral fiber that allowed Mary to say “do unto me as You have said” even though bearing God’s Son was going to cause all sorts of difficulty in her life… near divorce, etc. Very few words of Mary’s are recorded in scripture, and the line “she kept all of these things in her heart” lets us know there was a LOT going on inside despite her quiet nature. And, finally, all of us “Fannys” out there can draw some comfort in the fact that even though during this lifetime we may go unnoticed and unappreciated, God sees us… and will make sure everyone else does too in the end, even as He has done for His handmaid, so Full of Grace!

I just discovered your blog from The Habit of Being and I enjoyed this post very much and think you hit the nail on the head. I remember really liking Fanny the first time I read the novel and less the second time. I never really gave it much thought, though, as to why. I’d love to read it again.

And I enjoyed poking around on your blog. I do believe I’ll be back!

Brilliant post, Haley! I have always loved Fanny and it’s nice to see someone else sticking up for her. To me she always represented unwavering virtue.

I have had so many arguments with people over whether or not Fanny should have participated in that play. I always take her side and most people, even if they like the novel, do not. We just can’t apply modern standards to Fanny to understand her!

The thing that got me when I reread it this time was that I was not so impressed by Edmund and not as excited about he and Fanny getting married at the end. I didn’t think he deserved her. But I guess Fanny can judge better than me in that situation :-).

She is a realistic portrayal of an introvert does not = we should like her. Introverts in general are going to be less interesting protagonists simply because they will not do things when we want them to, but that does not mean that they must be as irritating as Fanny Price. A judgy introvert can be fun, if the author imparts even a modicum of sass or bite to them. But Fanny’s mind isn’t anything like that. It’s just irritated and exasperated at the utterly horrible things happening around her, like people putting on a play, or, when she returns to her family, sunlight daring to peep into her home. (Yes, she complains about sunlight in England). Even if we assume that her moral education is actually one we are intended to admire, that also doesn’t mean we should like her as a character. As a human being in real life, yes. As a character in a novel, no. Humbert Humbert or Captain Ahab will always be much more interesting characters than the upstanding protagonists of the kinds of novels you find in Protestant devotional shops.

I’m so eager to read Mansfield Park now, thank you!!

I’ve been trying to tell people this for years! You worded it so perfectly. Thank you.

I love Fanny’s strong convictions, humility and intuition as well. She’s not “entertaining” like you say, but she’s the kind of girl that I would love my daughters to be friends with.

Found your blog from the Motherhood and Jane Austen book club page on Facebook, which is also the only reason I read Mansfield Park, but I loved it. LOVED it. This probably colored my opinion a little bit, but my husband is a pastor, and so I found myself nodding in agreement with Edmund about everything it meant to be a minister. I also never could completely love Mary Crawford since she resented Edmund’s profession of choice. And I adored Fanny, and was rooting for her and Edmund the entire time. Towards the end, I thought maybe she would end up with Henry Crawford, and she and Edmund would just be cousins and in-laws, and I was trying to be okay with that, but I was so thrilled that the Crawfords turned out to be who I thought they’d been all along.

Quite randomly (in true Internet fashion) this is the second article about Mansfield Park that I’ve come across today. Here’s the first. This may be a sign that I need to go read it.

I don’t like Fanny Price for a few reasons – her inability to recognize both Edmund and her own flaws, her hypocrisy and her lack of growth. I don’t have anything against a character that doesn’t grow . . . especially if that lack of growth serves the story. But Fanny’s lack of growth doesn’t achieve this.

More importantly, Mary Crawford does have her flaws. In truth, she reminds me of the Dolly Levi character from “HELLO DOLLY” . . . likeable, manipulative, warm and ambitious. Mary is a well written balance of flaws and virtues. And yet . . . we’re supposed to dislike her? I don’t think so.

I think I’m confused by what you refer to as “Fanny’s hypocrisy”. Could you explain that? Thanks!

I agree with the posters who have said it is Fanny’s hypocrisy and judgment of others that makes her difficult to like and not the fact that she is shy and extroverted and put upon. For hypocrisy, I cite Fanny’s judgment of the play but her enjoyment of it throughout and the fact that she was just about to participate in it but was saved by the arrival of her uncle home.

For judgment of others, there’s a lot, but the worst part for me is how she is with her family in Portsmouth. In one particular scene, it’s said that she can’t bear to eat with them because of their coarse manners and the fact that the two maids-of-all-work (ie slave women) don’t clean the plates as well as she likes and is used to. Instead, she has to send out one of her brothers to buy her food. I can’t believe that she insists on getting the same standard of service at her mother’s house, where 2 maids (ie slave women) wait on a family of a dozen people, as at her aunt’s house, where 40 servants tend to a family of about 3-7!

i felt sorry for Fanny that she was transplanted away from her own family initially, but it’s clear that it’s a good thing because Fanny far prefers the trappings and comforts of wealth to strong, human relationships and being with your nearest and dearest.

Yes, her father is a drunk and her mother is a slattern and neither are capable of providing her with the love and comforts she yearns for. But she doesn’t get much of that at Mansfield Park, either. As someone pointed out above, Lady Bertram would do no better and probably worse in her mother’s circumstances, yet Fanny likes Lady Bertram far better. Why? Because she’s rich and sheds the comforts of wealth on Fanny.

Through Fanny’s eyes, and her judgment, the Prices are made out to be deplorable, heinous, disgusting people. She has no compassion for her mother’s plight — being born wealthy and pampered, but ending up the wife of an unemployed drunk trying to hold together a family of 9(?) children. Not until Henry Crawford shows up and we see the Prices through his eyes do we see that actually, they may not be so horrible after all, they are actually kind of a colourful, picturesque clan.

There is another small but telling moment in the chapel at Sotherton where she laments that it is not as grand and glorious looking as she expected and Edmund has to explain to her that ostentatious displays shouldn’t be that important in matters of faith. Austen repeatedly drops these disturbing little moments in to elucidate Fanny’s character. You have to ignore all of them to see her as the unalloyed virtuous heroine, but I can’t.

I contrast her with Anne Elliott, who was ill-treated within her own family and made to feel small and insignificant. Yet Anne always finds a way to give to others and she is never a judgmental snob about it. She rekindles her friendship with the poor and not-quite-respectable widow Mrs. Smith and helps her. Anne Elliott is quiet and introverted, but she is also brave and selfless and giving. THAT is why she is a beloved Austen heroine and not Fanny.

I despise Henry Crawford and I think Mary Crawford is a charming but ultimately shallow woman. On the other hand, I am surprised when people paint Edmund as the virtuous one and Mary as evil incarnate. It strikes me that they are both equally bad to each other, that both fall for the other’s superficial appeal (they’re both good looking) then selfishly demand that the other person change without being willing to change themselves. So if Mary is bad, Edmund is just as bad.

In the end, I don’t think it’s a book with heroes. It’s more like a cautionary/morality tale. Fanny and Edmund end up together, but it’s certainly no great romance after overcoming hardships to be together. It seems they end up together by default, and then toe the line the rest of their lives. I see MP as Austen’s literary experiment, and I think reading it as a romance is a misread.

Just my opinion, though.

If many readers truly disliked Fanny for her introverted nature, leading characters such as Elinor Dashwood and Anne Elliot would also be disliked. I do not dislike Elinor and Anne. In fact, they are favorites of mine.

Fanny is another problem. I dislike the character because I believe she is a hypocrite, she remained blind to Edmund’s faults and her own, and she did not grow as a character. I am not referring to her ability to crawl out of her shell and express her unwillingness to marry Henry. I am referring to the other flaws I had earlier expressed – her blindness regarding Edmund and her hypocrisy. I’m sorry, but Fanny is a character I will never like.

Great analysis. I agree with everything you say about Fanny. I still don’t like her personality 100%, but I’ve always thought she is a great character and certainly worth the protagonist role. I’ve never been one of those who thought that Mary is the true Austen heroine of the book. However, I still find it in myself to like Mary.

I agree that she lacks morals and that she is selfish, but what is for her to do? She has to be charming and marry well, with or without substance, because her brother will certainly not take care of her forever. She will eventually need a husband. I do think her regard for Edmund is real. I think she truly likes Edmund, even if it is only because he is a novelty, a righteous man. She is shallow and selfish, but I don’t think that makes her evil.

And she was absolutely right about Maria. Even if it wasn’t right, a secret affair would have been over-looked in London society. In fact, Mary’s plan after they eloped is, if I remember correctly, pretty similar to Mr. Bertram’s plan. The only problem is that, as a woman, she should never have said that. And of course, a self-righteous and pompous man like Edmund Bertram would absolutely hate her after such an indelicate declaration, even if he thought the same.

Fanny is OK, but Edmund Bertram, oh God, I find Edmund plainly disgusting!

This article was so intriguing! I’ve never liked Fanny as she always seemed such a prig (but then again I’ve only read Mansfield Park once or twice, some years ago) but this article did make me think I’ve nominated it for Miss Dashwood’s “I’d Like to Share” series over at http://miss-dashwood.blogspot.com.au/2013/08/id-like-to-share.html

I’ve nominated it for Miss Dashwood’s “I’d Like to Share” series over at http://miss-dashwood.blogspot.com.au/2013/08/id-like-to-share.html

I think Fanny often fails to appeal to readers for a number of reasons, chiefest of which is that they often miss what Austen seems — to me, at least — to be trying to convey through her.

Fanny has little self-awareness. She dwells on the moral lacks in everyone she meets; she points up the failures of the Bertrams as parents in not having attended to the formation of their children’s moral characters and her own parents’ failure to provide moral instruction, lessons in deportment and an orderly environment. At first glance the reader can only concede that Fanny must indeed be infinitely superior to all of these people to have reached such a pitch of moral perfection with no help at all. Fanny acknowldeges herself to have faults, but only those that would excite sympathy: she’s too sensitive, too selfless, too timid. Her inner dialogue repeatedly assures the hearer of her humility, but as frequently shows she believes herself the natural superior of everyone around her, including Edmund, who fails to at once share her opinion of Mary Crawford. (He does, of course, learn that Fanny was right.)

She seems oblvious to the reality that she shares some of the faults she condemns in others. She disapproves of concern for income in potential marriage partners, but misses the lifestyle only possible to wealth keenly and becomes apprehensive about being left in Portsmouth indefinitely. She feels her intelligence is too high and her nature too sensitive to bear such a disordered household and the company of such inelegant people, and removes herself as much as possible from the company of all but William and the sister she believes to resemble her. She views her family as the Bertrams viewed her on her arrival at Mansfield, and for the same reasons, but while she saw the Bertrams as snobs, she doesn’t see herself as having become one.

Fanny is a hypocrite: she condemns Mary Crawford for speaking less than respectfully of the uncle who raised her, but since said uncle had moved his mistress into his house after his wife’s death, Mary had no reason to speak of him with respect. Fanny not only approved the hypocrisy that condemns only public acknowledgement of an immoral behavior, not the behavior itself, but since she disparaged Mary only to Edmund, her motive was far from pure. And while she goes on about the inappropriate behaviour of other people, she doesn’t think it at all inappropriate for Edmund to coerce an invitation for her because she wants to see a house she wasn’t invited to.

Fanny has no sense of humour, no sense of the absurd. The difference between her feelings for her mother and her affection for her aunt – which becomes more intense as her anxiety about being left with her family permananently becomes more acute — is quite comic, since Austen makes it very clear that the only difference between Fanny’s mother and her aunt is in how far their husband’s income protects them (and their families) from their own ineffectuality. Even if Fanny doesn’t, the reader understands that were the positions reversed, Mrs. Bertram would be as inept and ineffective a parent and housekeeper as Mrs. Price. But that comic touch only points up the stark object lesson the two women provide in what happened to a woman who set her own judgment against that of society.

Fanny sees no similarity in attempting to better a financial position through marriage and her own family’s attempts to benefit from being related to Sir Thomas. I think with that Austen was making two points: we all view behaviours differently when we’re the ones engaging in them, and Fanny’s ‘blindness’ on this point was, for the poor of her time, particularly women, a hypocrisy of necessity. Austen, her sister and their mother were all dependent on the Austen sons for financial support: a refusal to take her brothers’ money would have been very high-minded in theory, but led to very straitened circumstances in practice.

Austen said “pictures of perfection make me sick and wicked”, and Fanny epitomizes perfection: she’s always right; everyone is, by the end, obliged to acknowledge her intelligence, purity, selflessness, etcetera. She’s so perfect that she can’t be allowed to the imperfect Henry Crawford; she may only be mated with the equally moral, if not equally intelligent, Edmund. She’s so relentlessly perfect that a reader can feel that Austen is determined to bludgeon the reader into loving her and resent being so autocratically told which character to care for. But despite their perfection, Fanny and Edmund share a crucial lack: they’re both genuinely well-intended people who want to be virtuous themselves and want others to be virtuous, but they are and remain incapable of making virtue attractive to others.

Mary Crawford is, imo, the insertion of Austen into her story: her morals are far from perfect, but she’s self-aware and capable of humor and candor, and is at least neither a Pharisee nor a hypocrite. She’s attracted to virtue in the person of Edmund, only to discover that his virtues don’t include the nerve to acknowledge the real moral standards of the society they live in and discuss what could be done about them. She behaves as her society approves of a woman behaving, but with a fine shade of excess that indicates she is merely doing what she knows a woman must to do enhance and retain her value in the marriage market.

By being opposites in so many ways, Fanny and Mary in a sense represent all women of Austen’s time: for as different as they seem to be, they are in the same position in terms of societal expectations and ability to ensure their own financial security. Mary appears to have more independence than Fanny has because of her income, but in reality both have limited agency: neither are permitted the freedoms permitted men; neither may ever make unrestricted use of their intelligence and talents. Their future status and security will be determined by the same thing: the social status and the income of the man they marry. Mary embodies the socially desirable: she’s lovely, intelligent, educated, witty, charming, sophisticated, realistic about social expectations and reactions, and wealthy. Fanny personifies personal perfection: she’s intelligent and educated, capable of forming her own opinions but willing to accept instruction; she’s pretty, but not vain; she’s honest, considerate, physically frail and unquestionably chaste. But neither Mary nor Fanny, despite all the qualities that make them ideal candidates for marriage (at least in Austen’s time), are guaranteed that they will marry or will marry someone for whom they could feel respect or affection. The results of a marriage without them Austen makes very clear, but she also makes it plain that women had little choice but to risk a lifetime in such a marriage and no means of altering the society in which they had such little real control of their lives.

Mary, who in a sense serves as the voice of society, often says aloud what everyone but Fanny and Edmund is thinking: e.g. that if the affair had not been made public property, no one would have cared about it. Fanny and Edmund are both aware that what Mary says is true, but Edmund is appalled that she should say it. His unwillingness to openly acknowledge the real moral standards of the world his parishioners would be living in does not bode well for his future as a minister, so Austen makes a final point: even a woman’s marrying a man of apparently excellent moral character didn’t guarantee her happiness in marriage. If a man is unwilling to have reality openly acknowledged, how long could any woman, even an ideal one, respect him? And if she couldn’t respect him but did respect herself, how could she be happy with him?

I may be reading far more into Mary and Fanny’s characters than Austen intended, but if there isn’t more to them than is immediately apparent, Fanny’s just a Mary Sue, and she and Edmund will spend their lives assuring each other of their moral superiority to everyone who ever crosses their path. I can’t imagine the point of creating such a dismal pair of prigs: in the words of Charles Dickens, “Between the Musselman and the Pharisee, commend me to the first.” The best anyone would be able to say of Mansfield Park is that people like Fanny and Edmund deserve each other, and Austen apparently was smart enough to know it.

This is probably the best article or post I have ever read about Fanny Price, Mary Crawford and Edmund Bertram.

Fantastic analysis. You’ve put your finger on it.

I don’t agree that people dislike Fanny because she is shy and introverted. There are lots of very beloved shy and introverted characters in fiction. E.g., Anne Elliot.

People dislike Fanny because of her holier-than-thou attitude and the fact that she is quite hypocritical and judgmental of others. Elizabeth Bennet and Emma Woodhouse are very flawed heroines, but they are both saved by their big hearts (Elizabeth for her sister Jane, Emma for all women except the hideous Mrs. Elton.) By contrast, Fanny seems quite self-centred in pitying herself, but having little compassion for others. Even the kindness she shows for Mr. Rushworth is tempered by the fact that she seems to view him with contempt.

I pity Fanny for her cruel upbringing, but I don’t find much to admire in her character.

I’ve been waiting to come back and post this comment now that the novel is finished and the not-so-secret source has been officially revealed, but MrsDarwin of Darwin Catholic has been writing Stillwater, her modern re-imagining of Mansfield Park. It is absolutely amazing! Your commentary on the novel is so close to hers that I assumed you knew about it already and weren’t mentioning it to avoid letting the cat out of the bag. But just in case I’m wrong, here’s the link http://darwincatholic.blogspot.com/2014/08/stillwater-index.html?m=1

http://darwincatholic.blogspot.com/2014/08/stillwater-index.html?m=1

I literally love so much that this article has been written. Mansfield Park has always been my favorite of Jane Austen’s books. The depth and complexity of her characters, and the importance of moral substance in this book are just amazing. I’m having trouble formulating words on how much I love it. Thank you so much for this.

I just read MP for the first time. I will say that from the beginning I found Fanny to be intriguing due to the situation she came from and the situation she was placed into. She sort of broke my heart as the ten year old Fanny and then Edmund coming to the rescue with the foresight he had at such a young age is when his heroism really shined for me. Being able to understand she needed love when he wasn’t necessarily brought up around others who really paid attention to the feelings of others was so endearing. So really from the start the two of them were set as the heroes for me. I think this was enough for me to be ok with how things progressed and to look past their somewhat not so stereotypical heroic characteristics.

I’ve often wondered how anyone torn from their family and thrust into the home of people who view them as a burden and an expense and a source of free labour could possibly become a dynamic exciting heroine that many condemn Fanny for not being. If a person is verbally and emotionally abused from tender formative years and harangued continually to be grateful for the abuse, is it any wonder poor Fanny does not come out of her shell. She was conditioned to believe that she did not deserve better treatment than she received. Just ask an abuse survivor and probably many would agree that the mental games abuser s play do have a concrete effect on shaping personality. Think of the constant fear she lived under; she was punished and neglected for nothing at all. I think it’s natural that Fanny should love Edmund as he seemed to be the only person who showed her the milk of human kindness at the most traumatic time of her young life. Of course he is flawed, but he is genuinely kind and takes up his calling to serve others with genuine heartfelt motives of virtue. Fanny’s strength shows itself quietly in spite of her abused and lonely life. Always the outsider ; always fully aware that she was “not a Miss Bertram”-but a person of no account, to be disregarded except to be used shamefully and thrown aside like a used handkerchief; until required again. Fanny and Edmund find and cling to each other as islands of goodness among a sea of moral laxity. Bravo to them both,even if they are not exciting and vivacious characters. Nice people deserve to have a half ending too; not just the glamorous.

I love Mansfield Park! It is actually one of my favorite Jane Austen novels! I think you stated exactly what Mansfield Park is about. Most people are so focused on the characters that really move our emotions and are dynamic instead of the steady characters. When I was younger I connected a lot with Fanny, and felt like her in many ways. It is nice to read about someone that likes Mansfield Park when a lot of people that I do know do not like Fanny or the book that much.

When I think of a heroine, I have always imagined a woman of both strong and sweet personality traits. Although Fanny Price is painfully shy, her good moral judgment makes her a great heroine. Like mentioned above in previous comments, Jane Austen’s heroines tend to go through a transitional turning point in their lives, however, Fanny seems to be the most constant character which shows to me how loyal of a person she is. Being once a shy person myself when I was younger, I learned to be much more social and accepting (towards myself and others). With characters like Fanny and Anne, I have a sweet spot for them because it takes me back to the person I used to be. Although shy heroines are not the favorites, I feel they are very genuine women who needs a bit of appreciation :p

You’re right, Fanny doesn’t really have that moral crisis. In this book, it’s Edmund, the hero, who has the crisis and changes. That’s what I think is so brilliant. Edmund starts out the superior, but then he must learn from Fanny.

Hi!

So this changed my perspective with this book. Don’t get me wrong, I’m a Jane Austen ADDICT, but “Mansfield Park” really was my least favorite Austen book. I guess I just need to read it again with a fresh perspective!

Oh I’m so glad, Lydia! Totally understandable, though, because MP really has a VERY different feel from the others.

I think you’d enjoy reading this essay by the literary critic Lionel Trilling if you’re keen on defending Mansfield Park from its detractors. I love his take on Austen’s novels and found this one on Mansfield Park to be really interesting. I was able to find it online here. Hopefully the link works for you! (I had to reload a couple times….)

http://www.unz.org/Pub/Encounter-1954sep-00009

“Austen said “pictures of perfection make me sick and wicked”, and Fanny epitomizes perfection: she’s always right; everyone is, by the end, obliged to acknowledge her intelligence, purity, selflessness, etcetera. She’s so perfect that she can’t be allowed to the imperfect Henry Crawford; she may only be mated with the equally moral, if not equally intelligent, Edmund. She’s so relentlessly perfect that a reader can feel that Austen is determined to bludgeon the reader into loving her and resent being so autocratically told which character to care for. But despite their perfection, Fanny and Edmund share a crucial lack: they’re both genuinely well-intended people who want to be virtuous themselves and want others to be virtuous, but they are and remain incapable of making virtue attractive to others.”

I have never regarded Fanny or Edmund as perfect. Like other characters, they had their own set of flaws. The problem is that Austen never allowed them to become aware of their flaws. Worse, this inability to sense their own flaws have led Fanny and Edmund to possess a lack of tolerance toward the flaws of others.

Another problem I have with the pair is that they are too alike. It is one thing to share “some” interests. But they’re too alike. There is something almost narcissist about the idea of a romance between Fanny and Edmund. And this “sameness” seems to render their relationship rather placid . . . almost flaccid. There are no contrasts or potential conflicts that will enable them to grow as individuals and as a couple. Their relationship will remain mired in what it had been since childhood . . . Fanny being Edmund’s emotional lap dog.

[“Fanny Price might be nearly impossible for our culture to understand, but that’s why we need her more than ever.”]

I don’t think so. There is something excessive, judgmental and rather hypocritical about Fanny Price, Edmund Bertram and Sir Thomas Bertram that I find off-putting.

I’m reading Mansfield park for the first time. I disagree that Fanny’s shyness is why she’s hard to love. Anne Elliot was quiet and observant. For me, Fanny is stubborn. She is so stubborn about Henry Crawford, who I must admit I was charmed by him and rooting for him a little.

And I may be biased because although for the time cousins marrying was not unusual it’s still kind of icky to me.

Mary Crawford would not have been a better heroine. Too calculating, she’s not relatable… To me anyway.

Thanks for sharing your theories!

Oh, and I can’t stand it when people conflate Elizabeth Bennet and Mary Crawford as essentially the same, can you? “What are men to rocks and mountains?” “I hope I never laugh at what is wise or good.” Mary Crawford is a version of Elizabeth that is totally bereft of character. They are superficially similar but essentially so different.

As much as I disdain Mary Crawford, I think she has one of the most memorable lines in all of JA’s works: “Nothing tires me except doing what I do not like.” I often quote that one to my choleric son.

I am thinking, is something wrong with me?, because I’ve always loved Mansfield Park and Fanny is my favourite Jane Austen’s heroine I’m surprised that the other people don’t like her!!! I identify with Fanny, I think I am someone between and introvert and extrovert, and I’m also extremely shy but that depends on the situation. I adore Fanny so much because she always does the right thing, no matter what are the demands of the others. And she reminds me of Molly Gibson from “Wives and daughters” by Elizabeth Gaskell.

I’m surprised that the other people don’t like her!!! I identify with Fanny, I think I am someone between and introvert and extrovert, and I’m also extremely shy but that depends on the situation. I adore Fanny so much because she always does the right thing, no matter what are the demands of the others. And she reminds me of Molly Gibson from “Wives and daughters” by Elizabeth Gaskell.

Haley,

I hope you don’t mind, but I borrowed a paragraph from your article and posted it on my blog. It is the clearest statement I’ve ever read of the theme of Mansfield Park..

High praise! Thanks, Fred

Great article! Am going to reread Mansfield Park soon and you’ve given me a lot to think about. I never considered Fanny’s situation. I guess part of her severe ‘priggishness’ is because she doesn’t actually have the freedom to do whatever she likes? She was in a pretty precarious situation, and I think I might like her more now that I see that new dimension to her character. Hey, have you seen From Mansfield With Love? It’s a webseries. Would love to hear your thoughts about it!

What do you mean that we “should” like “Mansfield Park”? Why? Because you liked it or Fanny Price? Why would you write an article arguing that anyone who reads it should share your opinion? I don’t understand that kind of mentality.

Yikes. It’s too bad that it’s difficult for you to imagine writing a post on your personal blog about something you really love in hopes of persuading others to love it, too. Not really sure how to help you here because it seems pretty self-explanatory. If this concept remains really difficult for you to understand, you might consider not reading what I write on my blog and taking care to avoid any sites that feature opinion pieces or persuasive writing. Best of luck to you!

I just read Mansfield Park again. Each time I read Jane Austen I fall in love with her ability to understand depression and anxiety and write about it in such a way that I feel for her characters. Fanny Price and her suffering touch me deeply, especially when her uncle makes her feel wretched for not accepting Henry Crawford. I felt wretched right along with her. I am a fan of Fanny. I love how Jane Austen writes her.

I know this is excessively late, and probably shall not be at all to the point, but I completely agree with your assessment of Fanny as a heroine, as well as we as a society. I am often startled, though not surprised, when others totally miss the whole point of Mansfield Park: form vs. substance.

Also, even though this isn’t necessarily “canon”, I have always read Fanny’s character with a modern understanding of mental illness and PTSD. Her inner monologues, full of self-deprecation; her extreme nervousness and emotional fragility; her exceeding reticence to speak her own mind, even from the first; these all seem to indicate a mind already prone to anxiety and depression, made worse by her early home-life. I remember reading the Portsmouth section of MP for the first time; Fanny’s character suddenly made even more sense. Perhaps, if people in this century were to look at her in that light, she might be valued as she ought.